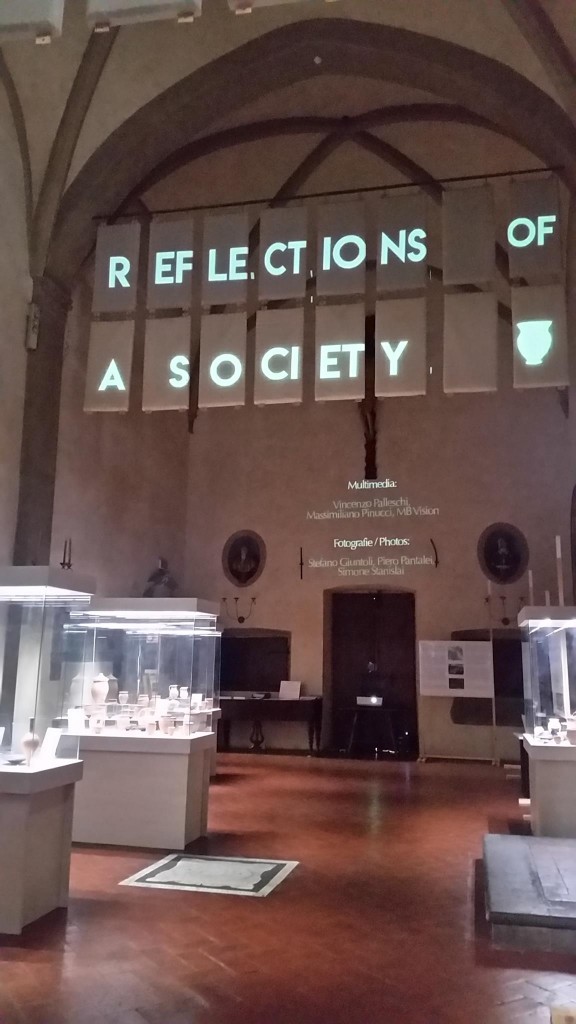

Church of San Jacopo in Campo Corbolini, Firenze

16 maggio – 29 giugno

By Katherine Reaume (Istituto Lorenzo de’ Medici)

Reflections of a Society, a temporary exhibition organized by CAMNES and the Istituto Lorenzo de’ Medici, displays the Telephus Mirror and other grave goods from the Etruscan necropolis of Macchia della Riserva in Tuscania (VT) from May 16th to June 29th. Held in the church of San Jacopo in Campo Corbolini open from 12 to 5:30 pm, there are a few large signs on display outside of the building, showing an image of the mirror. Though disappointingly the actual artifact is not on display inside, but a 3D replication and an explanation as to why the object is not present.

The overall exhibition provides information on who the Etruscans are along with where the artifacts were found. Information is given in both Italian and English, not only on the boards but also in several video displays. Unfortunately, the information panels at the entrance are hard to read due to the lack of light. The cases are set up by the location of where the objects were found in the grave site which is reflected and explained in the labels in the case. Yet, there is no correlation for the visitor to understand where each locali, or grave, is in correspondence to the overall tomb.

The visual displays are captivating and interesting, providing additional information not given in the written information panels. A downside is that these videos are not all in the best of locations. Upon first entering the exhibition the first video explains CAMNES and the dig site. In order to view the video comfortably, one stands in the middle of the pathway of the exhibition. The video explaining the Telephus mirror and the story behind it is also difficult to observe from up close due to the placement of the case in which the mirror is held. One must stand farther away and view the video then, go up closer to see the object.

Not only does this exhibition provide visual displays it also offers an interesting opportunity to view one of the tombs virtually. Donning a headset, one can enter the excavation site and look around one of the tombs during the process. Though interesting there is no interaction available within, one can only view the space. This virtual experience is not well advertised in the space, even though it is set up in the middle of the room on one of the altars.

Reflections of a Society also offers multiple learning opportunities, providing educational resources such as an activity booklet, bookmark, and brochure. This information can be found at the beginning of the exhibition and helps to enhance the experience for families and children. Overall the display of the artifacts is well done with ample amounts of informative material about Etruscans, and the site in which the artifacts were found makes this temporary exhibition worth a visit.

Traduzione di Tania Mio Bertolo (Università degli Studi di Firenze)

Riflessi di una società, la temporanea organizzata da CAMNES e dall’Istituto Lorenzo de’ Medici, espone al pubblico dal 16 maggio al 29 giugno lo “Specchio di Telefo” ed altri corredi funerari delle necropoli etrusche di Macchia della Riserva a Tuscania (VT) ed è visitabile ogni giorno da mezzogiorno alle 17:30. La mostra è ospitata nella chiesa di San Jacopo, all’esterno della quale si trovano alcuni grandi manifesti che mostrano l’immagine dello “Specchio di Telefo”. Spiacevolmente il manufatto originale non è esposto all’interno della mostra, ma è sostituito da una riproduzione tridimensionale corredata dalla spiegazione circa i motivi dell’assenza.

Nel complesso lo scopo dell’esposizione è ricostruire alcuni caratteri peculiari della civiltà etrusca partendo dagli oggetti ritrovati e dal luogo del loro rinvenimento. Le informazioni, sia in italiano che in inglese, non sono soltanto fornite attraverso i pannelli descrittivi ma anche per il tramite di alcuni fimati proiettati. Sfortunatamente i pannelli informativi posizionati all’ingresso sono difficilmente leggibili a causa della scarsa illuminazione. L’ordine espositivo dell’allestimento è determinato dalla posizione di ritrovamento degli oggetti all’interno dei “locali” dei siti funerari, e ciò è esplicitato nelle targhette corrispondenti a ciascuna teca; tuttavia non vi è possibilità per il visitatore di capire la posizione di tali locali all’interno delle tombe.

I video proiettati sono accattivanti ed interessanti, e forniscono informazioni aggiuntive rispetto a quelle date nei pannelli scritti; lo svantaggio è che questi filmati non sono posizionati nel migliore dei modi. Il primo filmato posizionato nei pressi dell’ingresso della mostra offre chiarimenti circa CAMNES ed il sito digitale, ma per poterne godere al meglio il visitatore è costretto ad allontanarsi verso il centro della sala. Anche il video dedicato allo Specchio di Telefo ed alla sua soria è difficile da seguire a causa della sua stretta vicinanza con la teca nella quale è esposto l’esemplare stesso: è necessario osservare il filmato da lontano, e poi avvicinarsi per ammirare lo specchio da vicino.

Ma la mostra non è costituita soltanto da filmati: essa offre anche un’interessante occasione per vedere virtualmente una delle tombe. Indossando le cuffie auricolari il visitatore può entrare attraverso lo spazio archeologico e osservare il sito funebre dall’interno. Benchè l’esperienza sia interessante, essa non è corredata da alcuna attività interattiva: il visitatore può solo osservare. Inoltre benchè sia posizionata al centro della sala, tale esperienza non è ben segnalata nello spazio.

Riflessi di una società offre anche molteplici occasioni di apprendimento, fornendo risorse educative attraverso un libricino per le attività, il segnalibro ed il pieghevole. Questo servizio è segnalato all’ingresso della mostra e favorisce un maggior coinvolgimento da parte delle famiglie e dei bambini. In conclusione, la disposizione degli oggetti è ben curata ed offre una grande quantità di materiale informativo sugli Etruschi e sui siti di ritrovamento degli oggetti, rendendo questa mostra quasi una visita ai siti originali.