Florence, Palazzo Pitti, Palatine Gallery

The Palatine Gallery and the Rooms of the Planets

An Immersion into Baroque Florence in the 21st century

By Camilla Torracchi (Università di Firenze)

For centuries Palazzo Pitti was home to the rulers of Florence, first the Medici, then the Lorraine, and finally the kings of Italy until 1919 when the palace was donated to the Italian state.

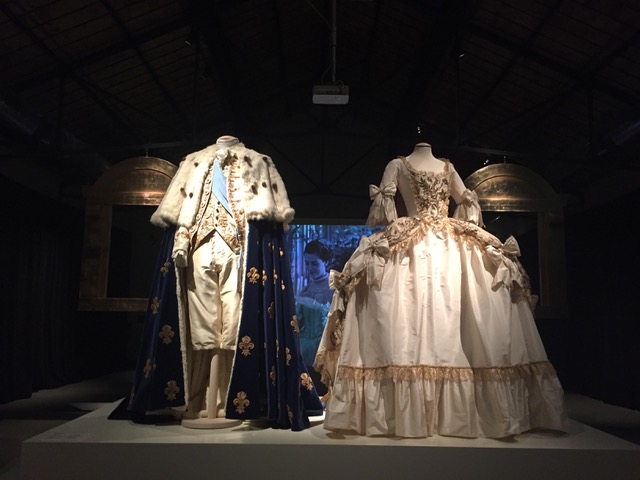

A place of power and display, to this day it is characterized by the richly decorated rooms with frescoed ceilings, white and gold stucco ornamentation, and sumptuously decorated walls covered in precious tapestries and fabrics.

The first floor contains the Palatine Gallery, a painting gallery opened to the public in 1828.

Between the end of the 18th and beginning of the 19th centuries the Lorena carried out various modifications inside the palazzo and the palace’s winter rooms were transformed into the painting gallery. The Lorena selected masterworks from the Medici collections to decorate the rooms according to 17th century painting gallery tastes. To this day the museum is characterized by its loyalty to maintaining the arrangement from the time in which it was opened.

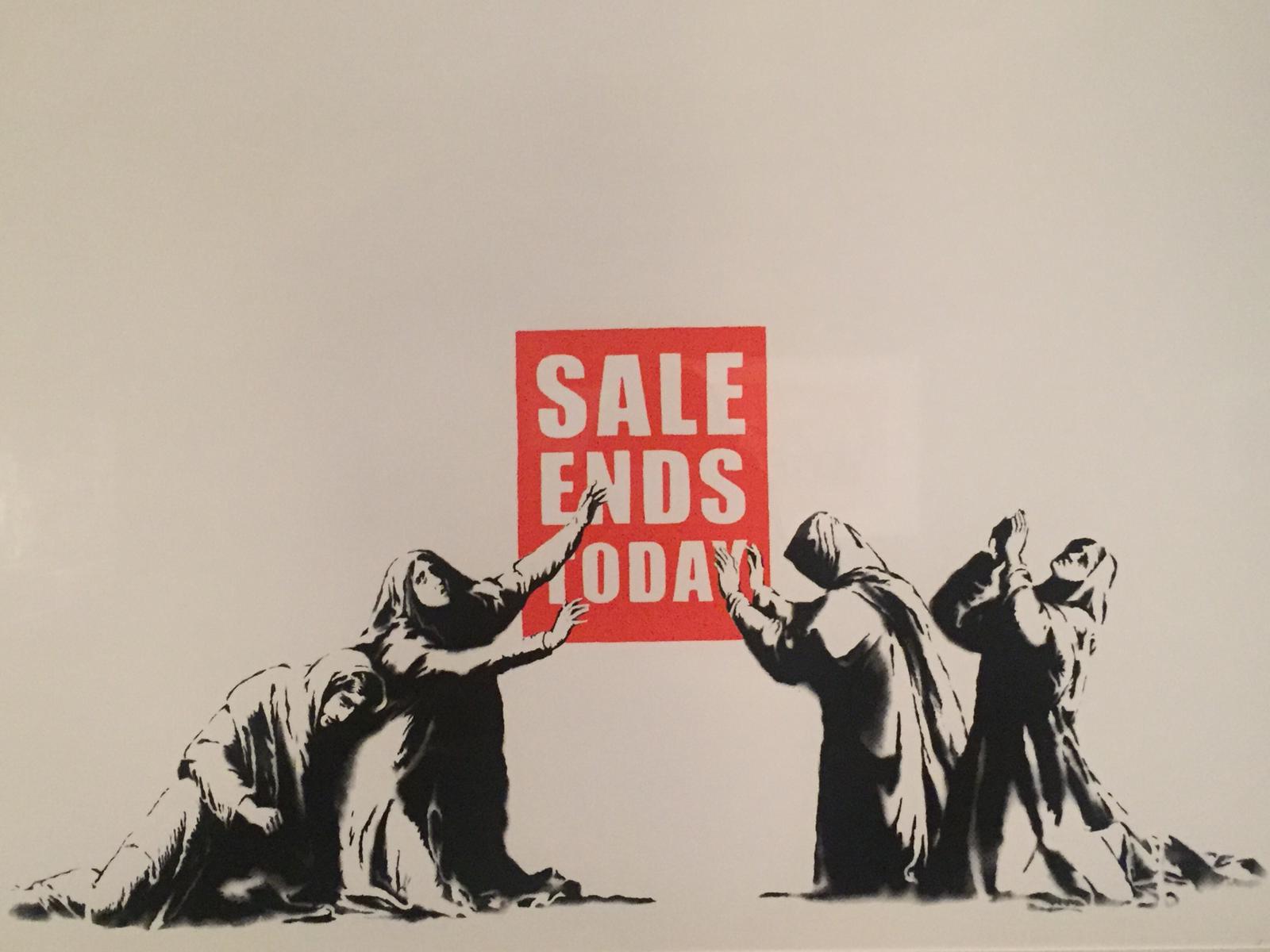

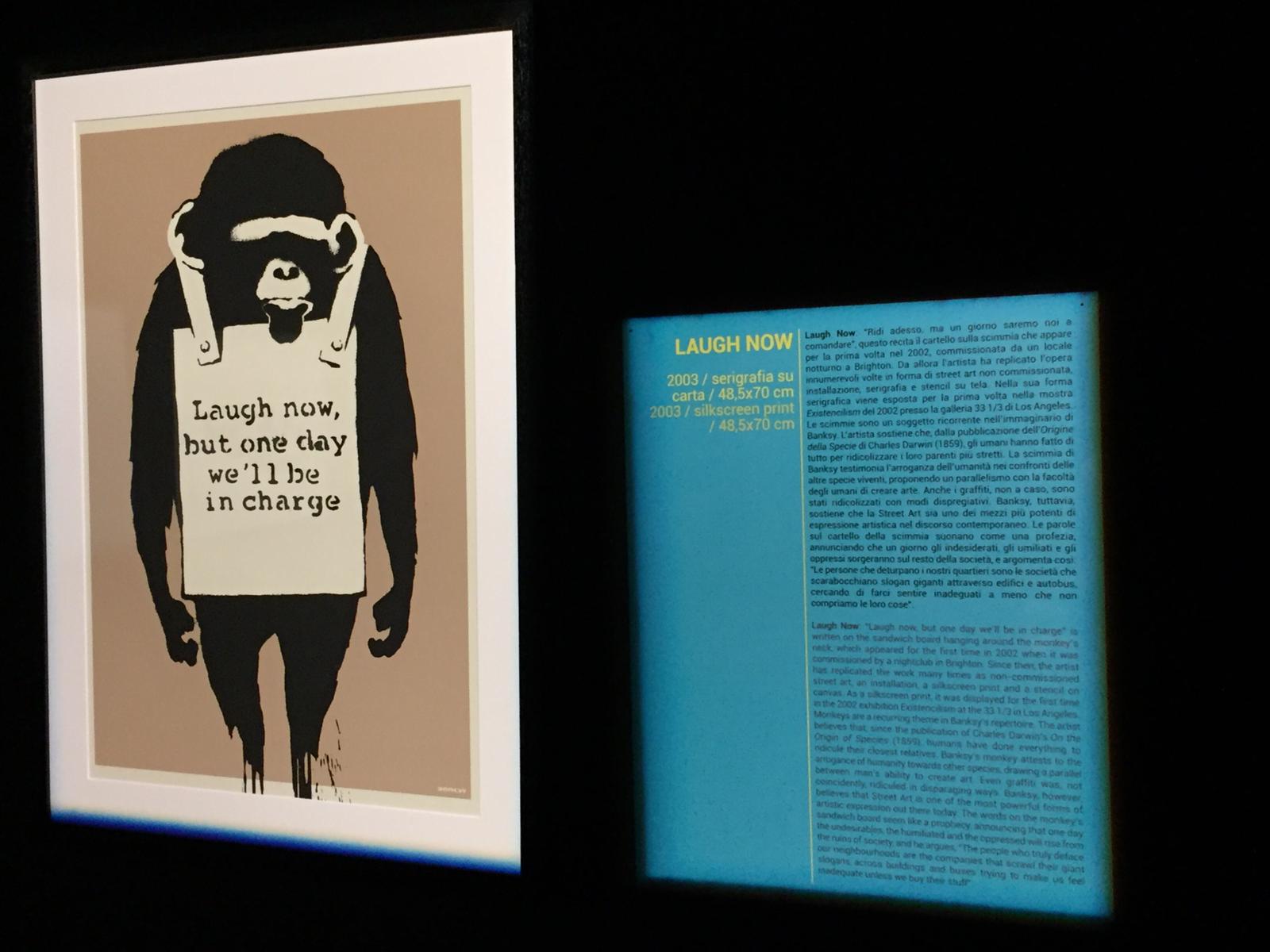

Visitors find themselves walking between the rooms whose walls are entirely covered in paintings hung on multiple vertical rows. This type of arrangement creates a strong scenography: the spectator is submerged in the abundance of works they are surrounded in. In fact, they do not find themselves in a gallery with partially bare walls, but with a huge quantity of works surrounding them, hung in splendid gilded frames. The paintings are in dialogue with sculptures and skillfully decorated tables realized in traditional artisanal Florentine school, a decorative technique defined by its valuable semiprecious stones.

Explanatory panels can be found in each room indicating the name of the room and its function inside the building both while the palace was occupied by the Medici and in the successive years. The visitor can thus be informed of the previous use of each space, how the building once appeared, and what changes the galleries have undergone.

The collection exhibited in the museum us rich with celebrated masterworks from notable artist including examples from Titian, Perugino, Rubens and Caravaggio. The painting gallery also is distinguished for holding the largest nucleus of Rafael’s works, concentrated in the so-called Saturn Room. August of 2018 foresaw movements of works between the Uffizi and the Palatine Galleries, during which Raphael’s Portrait of Julius II was brought back to the Palatine Gallery, Titian’s copy of which is also displayed in the gallery.

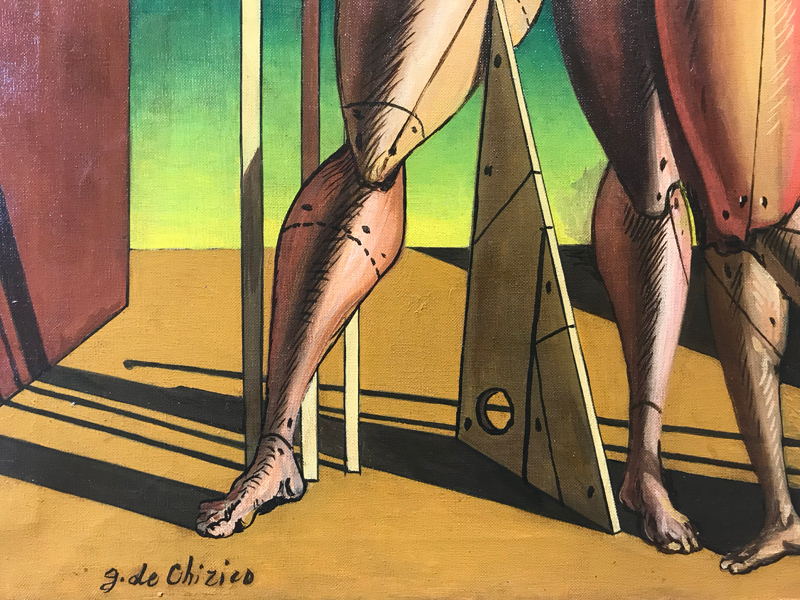

Included in the museum are the so-called Rooms of the Planets, one of the most important examples of Baroque painting in Florence. It is composed of five consecutive rooms that were frescoes for the Grand Duke Ferdinando II by Pietro da Cortona and concluded by his student Ciro Ferri in circa 1665. The name derived from the fact that every room is dedicated to a planet: Venus, Apollo, Mars, Jupiter, and Saturn. It was an interesting choice of theme that was connected to the four moons of Jupiter discovered by Galileo Galilei in 1610 and called the ‘Medicean stars’ in homage to Ferdinando II’s father, Cosimo II.

Every room contains a mythological scene decorating the vaulted ceilings which celebrate Ferdinando II’s rise to the Grand Duchy of Tuscany, and the prince is symbolically represented in the frescoes as Hercules. Moving between rooms visitors retrace idealised moments of a sovereign’s life. It begins with his adolescence in the Venus room and continues through to that of Apollo. They tell the story of the virtuous formation required to become a successful prince. The vault depicts Hercules, Ferdinando’s alter ego, supporting the terrestrial globe, a symbol of the responsibility that a sovereign must support. The Mars room eludes to the prince’s triumph in the art of war and culminates in the center of the ceiling with a crowned Medici crest inscribed with Ferdinando’s name. In the successive room the prince has finally concluded his apprenticeship, he is crowned by Jupiter and recognized as the legitimate heir of the Grand Ducal throne. In the last room, that of Saturn, the prince has aged and is waiting to be crowned by an allegory of Fame to join the realm of eternity.

The room of Saturn is the ideal conclusion to the celebratory path through Medicean glory, but is the first room that visitors enter reversing the museum path I in respect to the 17th century project.

Visitors can stroll through the works of art finding themselves immersed in a space in which the frescoes, thanks to their illusionistic perspective, seem to break through the roof, and in an environment reflecting a baroque painting gallery, evoking the splendid display of the Medici court.

Translation by Marie-Claire Desjardin (Istituto Lorenzo de’ Medici)

Firenze, Palazzo Pitti, Galleria Palatina

La Galleria Palatina e le Sale dei Pianeti

Un’immersione nel barocco nella Firenze del XXI secolo

Di Camilla Torracchi (Università di Firenze)

Palazzo Pitti ha ospitato per secoli i regnanti di Firenze, i Medici prima, i Lorena poi e i Re d’Italia fino al 1919 quando l’intero complesso fu donato allo Stato italiano.

Luogo di potere e di fasto, ancora oggi si presenta caratterizzato da sale riccamente ornate con soffitti affrescati, stucchi bianchi e dorati e pareti rivestite da decorazioni sontuose, come arazzi e stoffe pregiate.

Ospita al primo piano la Galleria Palatina, una pinacoteca aperta al pubblico nel 1828.

Fra la fine del Settecento e l’inizio dell’Ottocento i Lorena operarono alcune modifiche all’interno del palazzo e le sale disposte in facciata divennero la sede della Quadreria. I Lorena selezionarono alcuni capolavori provenienti dalle collezioni medicee allestendo le stanze secondo il gusto delle quadrerie seicentesche. Ad oggi il museo si caratterizza proprio per la fedeltà con cui ha mantenuto l’allestimento che presentava alla sua apertura.

Il visitatore si trova così a passeggiare fra le sale le cui pareti sono interamente coperte di dipinti disposti su più file verticali. Questa tipologia di allestimento produce un forte effetto scenografico: lo spettatore è così sommerso dall’abbondanza di opere che lo circondano. Non troviamo infatti in galleria pareti vuote, ma una gran quantità di dipinti racchiusi in sfarzose cornici dorate. I quadri dialogano con sculture e tavoli maestosi realizzati secondo l’arte del commesso fiorentino, tecnica decorativa di pietre dure di grande pregio.

In ogni sala vi sono dei pannelli esplicativi che indicano il nome della stanza e quale funzione essa svolgesse all’interno del palazzo sia in epoca medicea che successiva. Il visitatore può così essere informato sia sulle precedenti destinazioni d’uso di ogni ambiente sia di come dovesse presentarsi un tempo il palazzo e quali modiche abbia subito la pinacoteca.

La collezione esposta nel museo è ricca di celebri capolavori di noti artisti fra i quali ad esempio Tiziano, Perugino, Rubens e Caravaggio. La pinacoteca si distingue inoltre per ospitare il più grande nucleo di opere di Raffaello, concentrate nella Sala detta di Saturno. Nell’agosto del 2018 sono avvenuti alcuni spostamenti di opere tra le Gallerie degli Uffizi e la Galleria Palatina e in Palazzo Pitti è stato riportato il Ritratto di Giulio II di Raffaello, la cui copia realizzata da Tiziano è esposta nella stessa Galleria Palatina.

Comprese nel museo vi sono le cosiddette Sale dei Pianeti, uno dei maggiori esempi di pittura barocca a Firenze. Si tratta di cinque ambienti consecutivi fra loro, fatti affrescare per volere del Granduca Ferdinando II da Pietro da Cortona e conclusi dal suo allievo Ciro Ferri nel 1665 circa. Il nome deriva dal fatto che ogni sala è dedicata ad un pianeta: Venere, Apollo, Marte, Giove e Saturno. Interessante è la scelta del tema che si collega ai quattro satelliti di Giove scoperti da Galileo Galilei nel 1610 e chiamati “astri medicei” in omaggio al padre di Ferdinando II, Cosimo II.

In ciascuna di queste stanze, sulle volte, è raffigurata una scena mitologica che celebra l’ascesa al Granducato di Toscana dello stesso Ferdinando II e negli affreschi il principe è rappresentato simbolicamente come Ercole. Spostandosi da una sala all’altra si ripercorrono così idealmente i momenti della vita di un sovrano. Si inizia dalla sua adolescenza nella sala di Venere e si prosegue in quella di Apollo. In questa si tratta della sua educazione alla virtù per diventare un buon principe. Sulla volta si rappresenta infatti Ercole, alter ego di Ferdinando, che sorregge il globo terrestre, simbolo delle responsabilità che un sovrano deve affrontare. Nella sala di Marte si allude al trionfo del principe nell’arte della guerra e spicca al centro del soffitto lo stemma mediceo con sopra una corona e all’interno scritto il nome stesso di Ferdinando. Nella sala successiva il principe ha finalmente concluso il suo percorso formativo e viene incoronato da Giove e riconosciuto come legittimo erede al trono granducale. Nell’ultima sala, quella di Saturno, il principe è ormai anziano e attende di essere incoronato dalla Fama per raggiungere in cielo l’eternità.

La Sala di Saturno è la conclusione di questo ideale cammino celebrativo della gloria medicea, ma è la prima stanza che il visitatore vede poiché oggi il percorso museale è in senso inverso rispetto al progetto del XVII secolo.

Il visitatore può passeggiare fra le opere d’arte trovandosi immerso in un luogo in cui gli affreschi, grazie all’uso della prospettiva illusionistica, sembrano sfondare il soffitto, e in un ambiente che è lo specchio di una quadreria barocca, capace di evocare il fasto della corte medicea.

Traduzione di Camilla Torracchi (Università di Firenze)

Photo courtesy Camilla Torracchi