By Mackenzie Constantinou (Lorenzo de’ Medici)

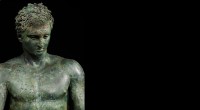

The title of Antony Gormley’s exhibition is highly evocative and intended to make the Forte di Belvedere represent humanity, through the medium of sculpture. While, it attempts to return the aspects that characterize the works.

Due to this, the Forte did not make a casual selection of works, since it is a place that requires a continuous confrontation with the view of Florence, a city that embodies the humanism, the Renaissance, and then the man himself.

Antony Gormley, an English Artist, was born in 1950. He also created brochure text. These pamphlets are handed out to the visitors, which help to explain the concept of the exhibition and provide more information on the main works.

Before entering the Forte, the visitor is presented with two sculptures that appear misplaced. Once up the stairs the visitor starts the journey of reflecting on man and humanity, while exploring the rooms of the building-in the old gunpowder storage room and upstairs that includes terrace-and throughout the garden.

Within the rooms the tension between the exhibition and the architecture is palpable. The statues become continuations of the walls. The works almost merge with the floor or are in the middle of the large windows from which the light filters through grates.

Outside the statues, casted in iron in various positions, echo and emphasize the multiple perspectives that allow the views of the Forte. In the form recognizably human or unstructured blocks, Blackwork, creates continuous contrasts and dialogues.

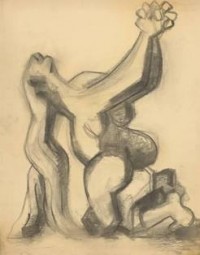

The reinterpretation of Critical Mass, a work of 1995, occupying the terrace overlooking the Forte creates a long diagonal where the statues are placed to create linear progression. In contrast, on the opposite side, the same poses lose their linearity in a set of bodies stacked on each other in an apparently random manner.

Reflection, listening, and prayer are all human actions that the sculptures repeat. They occupy every corner of the exhibition space, often almost surprising the visitor.

The striking, beautiful, and spectacular views contribute greatly to the reception of the works of Gormley which make the experience interesting and evocative.

Until September 27

Human, Forte di Belvedere.

di Carolina Caverni (Università di Firenze)

Il titolo della mostra è quanto mai evocativo di ciò che Antony Gormley ha inteso fare al Forte di Belvedere, ovvero rappresentare l’umanità, attraverso il medium della scultura, tentando di restituire gli aspetti che la caratterizzano.

Non è dunque casuale la scelta del Forte, luogo che presuppone un continuo confronto con il panorama su Firenze, città che incarna l’umanesimo, il rinascimento e quindi l’uomo stesso.

L’artista, inglese, classe 1950, ha anche realizzato i testi contenuti in una brochure consegnata al visitatore con il concept della mostra e le informazioni sulle principali opere.

Prima di accedere al Forte, ci si imbatte in due sculture che sembrano quasi lasciate li per caso, come abbandonate da qualcuno che debba tornare a prenderle. Una volta salite le scale la riflessione sull’uomo e sull’umanità si snoda attraverso un percorso sia interno agli ambienti dell’edifico – nel vecchio deposito della polvere da sparo e al piano superiore che include le terrazze panoramiche – che in tutto il giardino.

Nelle stanze interne il dialogo con l’architettura si fa serrato, le statue divengono prosecuzioni delle pareti, si fondono quasi con il pavimento, o sono al centro delle grandi finestre da cui filtra la luce attraverso grate.

All’esterno, le statue in ferro con le loro posizioni varie fanno da eco e sottolineano le molteplici prospettive che consente il panorama del Forte, in forma riconoscibilmente umana o destrutturata in blocchi, i Blackwork, creano continui contrasti e dialoghi.

La reinterpretazione di Critical Mass, opera del 1995, occupa la terrazza prospiciente al Forte creando una grande diagonale in cui le statue sono poste come a realizzare una danza in progressione lineare, in contrasto, dalla parte opposta, le stesse pose perdono tale linearità in un insieme di corpi accatastati gli uni sugli altri in maniera apparentemente casuale.

La riflessione, l’ascolto, la preghiera, sono tutti atteggiamenti umani che le sculture ripetono occupando ogni angolo dello spazio espositivo, spesso quasi sorprendendo il visitatore.

Il luogo suggestivo e la spettacolarità della vista contribuiscono notevolmente alla ricezione delle opere di Gormley rendendo l’esperienza molto interessante ed evocativa.

Fino al 27 Settembre