By Mackenzie Constantinou (Lorenzo de’ Medici)

The Museum of Zoology and Natural History, La Specola, is the oldest scientific Museum in Europe. Centrally located in Florence near Palazzo Pitti, this museum is housed in Palazzo Torrigani on Via Romana 17, and was founded in 1775 by the Gran Duke of Tuscany Pietro Leopoldo. The museum was created to house the curiosities found in world such as fossils, exotic animals, minerals, and fauna, creating a Wunderkammer, and it aimed to inspire and educate the public through its collection of works. La Specola is also one of the first scientific museums within Florence that has been continuously opened to the public since it was founded in the 18th century.

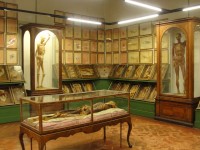

This museum holds a collection of natural curiosities such as fossils, exotic animals, minerals, and fauna, which are preserved in various ways, via drying and stuffing, and are displayed in glass cases. This collection highlights the great curiosities of the Gran Duke and the Medici family, and their attempts to understand natural phenomenons through observation. The museum is also renowned for its wax anatomical model collection, which also is partly displayed at Museo Galileo. These models were copied from real corpses and were highly labor intensive. All of the body parts from the cadaver had to be varnished and each needed a wax mold for duplication. These organs were then assembled into the torso then covered, so that the product was highly realistic. These models are important to understanding the known scientific theories of the time, and were used for medical teaching purposes as they offered a hands-on learning experience. Accompanying these models is a selection from the institution’s medical instruments; these are also displayed on the upper floor of the Museo Galileo. Since the remodeling of the Museo Galileo in 2010 there is a limited display of these wax models and medical instruments on the upper story, so if interested visit La Specola for a more complete view.

The wax models and the other objects within the collection are currently displayed in a historical context, meaning that they are exhibited in a similar manner to the way they were shown in the 18th century to the public. This display of older cases and a lack of labels could lead to a miscommunication with the audience, as they could possibly not fully understanding the significance of the works. However, this limited modernization of the display transforms the exhibition of these items themselves into a historic artifact, providing a view into the past. With the limited labels only depicting the technical scientific names for the works it conveys what the original collector would have been interested in by the collection. Due to the museum’s lack of educational materials to explain the works to the visitor, it is suggested that individuals obtain a guided visit or purchase a guidebook at the museum store. Either or these options would help the viewer gain a further understanding of not only the works but of their cultural and historical significance.

Overall, La Specola is a rich museum that offers a vast collection of natural wonders and wax models. Through the conscious decision of preserving the period display of the works the current visitor is transported to seeing the objects in the time period of the 18th century. For more information on the museum visit the website:

http://www.msn.unifi.it/visita/la-specola-torrino-salone-degli-scheletri/

Museo di Storia Naturale, Zoologia ‘La Specola’

By Carolina Caverni (Università di Firenze)

Il Museo di Zoologia e Storia Naturale, La Specola, è il più antico Museo scientifico d’Europa. Situato in centro vicino a Palazzo Pitti, si trova nel Palazzo Torrigani in Via Romana 17, e venne fondato nel 1775 dal Granduca di Toscana Pietro Leopoldo. Il museo venne istituito per ospitare le curiosità del mondo, come fossili, animali esotici, minerali e fauna, con la creazione di una Wunderkammer che mirava ad ispirare ed educare il pubblico attraverso la collezione di opere. La Specola è inoltre uno dei primi musei scientifici di Firenze che è stato costantemente aperto al pubblico da quando venne fondato nel 18 ° secolo.

Il museo ospita una collezione di curiosità naturali come fossili, animali esotici, minerali e fauna, conservati in vario modo, tramite essiccazione e imbalsamazione, ed esposti in teche di vetro. Questa collezione mette in luce le grandi curiosità del Gran Duca e della famiglia Medici, ed i loro tentativi di comprendere fenomeni naturali attraverso l’osservazione.

Il museo è anche rinomato per la sua collezione di modelli anatomici in cera, che è in parte conservata anche al Museo Galileo. Questi modelli sono stati copiati da cadaveri veri ed hanno un alto livello di manodopera. Gli organi sono stati poi assemblati in un tronco poi coperto, in modo che il modello risultasse molto realistico.

Questi modelli sono importanti per capire il livello di conoscenza scientifica del tempo, e sono stati utilizzati per scopi medici e didattici permettendo un’esperienza di apprendimento pratico.

Una selezione di strumenti medici che sono esposti anche al piano superiore del Museo Galileo gli accompagna.

A seguito della ristrutturazione del Museo Galileo, avvenuta nel 2010, vi è una collezione limitata di questi modelli in cera e strumenti, è quindi interessante visitare La Specola per una visione più completa.

Le cere e gli altri oggetti della collezione sono attualmente esposti contestualizzandoli storicamente, ovvero in un modo simile a come venivano mostrati al pubblico nel 18 ° secolo.

Questo allestimento degli oggetti più vecchi e la mancanza di didascalie portavano forse ad una cattiva comunicazione con il pubblico non rendendo pienamente comprensibile il significato delle opere.

Tuttavia, questa modernizzazione limitata dell’allestimento trasforma l’esposizione stessa di questi elementi in un manufatto storico, permettendo uno sguardo al passato. La limitatezza delle informazioni delle didascalie, che riportano solo i nomi tecnici e scientifici delle opere, permette di comprendere gli interessi originali del collezionista.

A causa della mancanza di materiale didattico si suggerisce ai visitatori di prenotare una visita guidata o di acquistare una guida nel negozio del museo. Queste opzioni potrebbero aiutare lo spettatore sia ad acquisire una maggiore comprensione delle opere sia del loro significato culturale e storico. Nel complesso La Specola è un museo ricco che offre una vasta collezione di meraviglie naturali e di modelli in cera. Grazie alla decisione consapevole di preservare l’allestimento originale il visitatore moderno è portato a leggere gli oggetti come nel 18° secolo.

Per ulteriori informazioni sul museo si visiti il sito:

http://www.msn.unifi.it/visita/la-specola-torrino-salone-degli-scheletri/