By: Rachyl Grussing

The Laurentian Library, located inside the Church of San Lorenzo, contains much of the collected learning of the Medici family. The library, designed by Michelangelo in 1534 and completed by Ammanati, has previously hosted exhibitions on the manuscripts found in the collection; the most current exhibition is in a similar vein. Entitled ‘ad usum fratris: Miniatures in the Laurentian Manuscripts of the Holy Cross X-XIII’, the exhibit, with the help of technology, focuses on about 53 illuminated manuscripts relating to ecclesiastical subjects and some manuscripts of a more pagan nature. These tomes are originally from the library of the Church of Santa Croce located across the city from San Lorenzo. The books were transferred to the Laurentian Library under the Grand Duke of Tuscany, Peter Leopold, in 1766, thus creating a collection of over ten thousand manuscripts.

The Library has made a herculean effort to include technology in this exhibition, and done an excellent job. Museums all over Italy have moved to integrate modern technology to make their collections more accessible to visitors. For example, Palazzo Blu in Pisa has included in their coin room a touch screen option to explore both sides of the coins visually and learn more about the coins and their history. Milan’s National Science and Technology Museum thrives on the inclusion of technology in their exhibits. Their newest exhibit about CERN includes electronic games, sounds, and touch screens to allow visitors different ways to fully grasp the concept of the particle. In Florence, the new Museum of the Duomo integrates videos into their experience as a way to give information to visitors about the Duomo, how it was made, and the making of this newer museum, rather than using the traditional reading of panel and exhibit text. This inclusion of technology to disseminate information is seen by many as the future of museums.

The exhibit in San Lorenzo uses scenes projected onto screens in the first room. These are close up photos of the illuminations on the manuscripts and aerial views of the city of Florence. However, the first thing that strikes the viewer upon entrance to the exhibit is the faint hymnal music playing. It is fitting; the first room houses biblical texts of the Medici family. The light is dim in the exhibition rooms for the sake of preserving these delicate manuscripts, and it enhances the air of age and importance of the texts. Dim lighting continues throughout all three rooms of the exhibition, although there is only music in the first room.

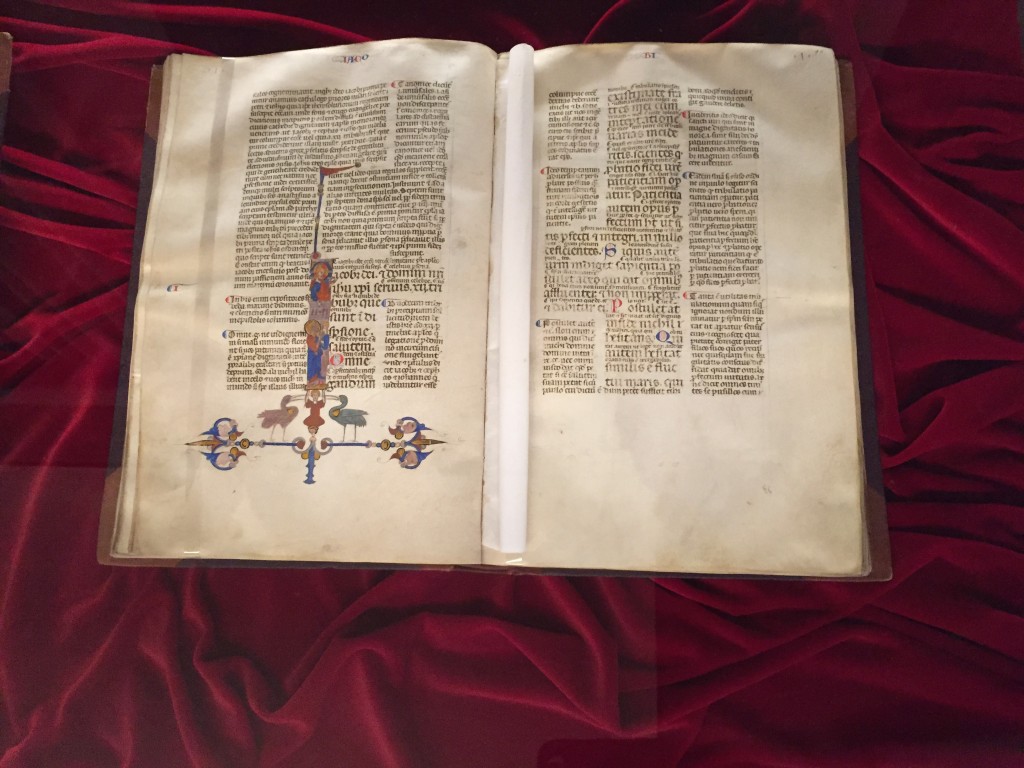

The labels identifying the manuscripts are small backlit paper labels, making them fairly easy to read. These backlit labels include only the bare minimum of information which leaves the visitor with more questions than answers. It seems as though the visitor is supposed to focus exclusively on the illuminations as pictures rather than learning about the importance of the manuscripts. The books themselves lay in clear glass cases, situated on what looks like lush red velvet. Extra information about the books comes in the form of a screen in the corner of the room, which features scrolling text about the books and their illuminations, but only in the most general of terms. It is hard to follow the text if one comes upon it while it is mid-scroll and the academic subject matter does not invite a guest to linger. If the text were a tad slower and the text easier to follow, it would enhance the visitor experience tenfold.

Not limiting itself to just rolling text, the exhibit has also two touch screens that allow the visitor more in-depth access to the manuscripts. The first screen gives a selection of categories, then allows you to zoom in on the illuminations on the manuscripts. The second touch screen in the exhibit has a larger selection of manuscripts to zoom in on, but the mechanisms are harder to use. It is possible to ‘flip’ through the book and read, but most of the texts are in Latin and there has been no attempt to translate the works for the visitors who do not know this language. There is no textual context for the illuminations, it simply allows an up close and personal experience with the delicate and fantastic drawings. If the curators had selected a few texts and gone in depth with what the text was and why the illuminations were important it would have enhanced the experience.

All in all, the exhibit seems to be an attempt to forge together the past and the present. The manuscripts themselves are beautifully illuminated and presented, and the technology integration is good, but the information provided via technology has missed the mark. The visitor leaves the exhibit having learned nothing about illuminations in manuscripts, which seems a shame. While an excellent idea, merely having the technology in place does nothing if it does not enhance the museum visit. A better use for the technology in the exhibit would be to explain why these illuminations in these particular manuscripts were chosen and answer some questions: Are they particularly good illuminations? Are the manuscripts themselves valuable? How do these illuminations relate to the text? With the technology already in place answers to those questions could have been used to educate the visitor in the mechanisms behind these manuscripts, rather than having the visitor to focus on the ‘pretty pictures’.

Traduzione di Tania Mio Bertolo

Nel complesso monumentale di San Lorenzo a Firenze, e precisamente negli ambienti della Biblioteca Laurenziana, sono ancor oggi conservati i codici miniati appartenuti alla famiglia dei Medici. Proprio in questi giorni la detta Biblioteca, l’edificazione della quale fu progettata ed avviata da Michelangelo e poi ultimata dall’Ammannati, ospita una mostra dedicata, come già in passato avvenne, ad alcuni volumi ivi raccolti. L’esposizione “Ad usum fratris: Miniature nei manoscritti laurenziani di Santa Croce (secc. XI-XIII)”, l’allestimento della quale si serve dell’aiuto di strumenti tecnologici, presenta una selezione di 53 codici miniati di argomento religioso e pagano, già appartenuti alle raccolte della Basilica di Santa Croce e trasferiti per volere di Pietro Leopoldo nel 1776 nella Biblioteca Laurenziana, dove ad oggi è conservata una collezione di oltre dieci mila esemplari.

Ai curatori va riconosciuto il notevole sforzo compiuto per includere apporti tecnologici nell’allestimento, ottenendo così un ottimo risultato. Difatti i musei italiani stanno oggigiorno progressivamente integrando i loro percorsi espositivi con strumenti multimediali finalizzati a rendere le proprie collezioni maggiormente accessibili: ne è un esempio il chiosco interattivo allestito nella Sala del Monetiere di Palazzo Blu a Pisa, un sistema digitale touch-screen che permette sia di visualizzare le monete da entrambi i lati, sia di ricercarne informazioni. Anche il Museo Nazionale della Scienza e della Tecnologia di Milano sta incrementando l’utilizzo di sistemi multimediali: l’allestimento della sua nuova esposizione permanente, realizzata in collaborazione con il CERN, fa ampio uso di giochi elettronici, suoni e schermi digitali che offrono l’opportunità di un approccio più diretto allo studio delle particelle, oggetto della mostra. A Firenze inoltre, nel nuovo allestimento del Museo dell’Opera del Duomo, documentari filmati inerenti la cattedrale, la sua storia e la recentissima messa in opera dello stesso museo, hanno preso il posto dei tradizionali pannelli informativi.

Per quanto concerne la mostra ospitata alla Laurenziana, l’allestimento della prima sala propone una proiezione di foto relative sia alle miniature dei codici, sia alle vedute della città di Firenze. Ciò che però colpisce maggiormente all’ingresso è il sottofondo musicale in armonia con i testi biblici di antica appartenenza medicea qui esposti. Pertinente è anche la scelta dell’utilizzo di una luce soffusa, utile sia a salvaguardare questi stessi delicati manoscritti, sia a sottolinearne l’antichità ed il pregio storico. La medesima illuminazione soffusa prosegue nelle successive tre sale, la musica invece si ferma al primo ambiente.

Le targhette identificative sono piccole ma retroilluminate, facilmente leggibili. Tuttavia esse riportano poche informazioni, non sufficienti per saziare la curiosità del visitatore. Anzi, sembrano quasi invitarlo a soffermarsi maggiormente sull’aspetto visivo delle miniature piuttosto che su quello storico o tecnico, appunto scarsamente esplicitato nelle targhette stesse. I manoscritti sono esposti all’interno di teche di vetro, e sono appoggiati su drappi di velluto rosso. Nozioni aggiuntive vengono fornite attraverso uno schermo collocato in uno degli angoli della stanza nel quale un testo scorrevole spiega, purtroppo solo in termini generici, le peculiarità dei volumi e delle miniature. Trattandosi appunto di un testo scorrevole che perlopiù tratta un argomento estremamente accademico, il visitatore accostatosi allo schermo a proiezione già avviata può trovare difficoltà nella comprensione del discorso. Uno scorrimento più lento della proiezione e un testo più accessibile faciliterebbero l’approccio e renderebbero la visita più piacevole.

Oltre allo schermo con testo scorrevole, l’allestimento prevede anche due touch-screen utili a comprendere più a fondo l’arte miniata: uno offre una selezione di categorie per ingrandire le immagini delle miniature; l’altro, che usa un sistema non facilmente comprensibile, permette invece di visionare in modo ravvicinato un più ampio ventaglio di manoscritti. Per mezzo di esso il visitatore può selezionare a suo piacimento le carte da osservare e i brani da leggere, ma non è fornito nessun supporto a chi non conosce il latino, lingua con la quale furono compilati questi manoscritti. Manca anche una contestualizzazione testuale degli esemplari visionabili tramite questi schermi, strumenti che in definitiva garantiscono soltanto un più alto livello di personalizzazione dell’esperienza del visitatore. Se i curatori avessero selezionato un numero inferiore di testi ma avessero fornito maggiori informazioni storiche e tecniche su di essi, motivando anche il criterio di selezione delle miniature esposte, la visita sarebbe più piacevole.

Per concludere, la mostra sembra essere un tentativo di unire insieme passato e presente. Da un punto di vista museografico, valide sono le scelte di illuminazione e di presentazione degli esemplari. Ben pensato è anche l’apporto multimediale, ma le informazioni fornite sono scarse e incomplete: il visitatore esce dalla mostra avendo appreso ben poco sulle miniature. Purtroppo gli strumenti tecnologici, quando non sono funzionali, non arricchiscono il percorso museale. Essi, se fossero stati usati intelligentemente, avrebbero spiegato i motivi e le finalità della mostra, e avrebbero risposto a domande circa il reale valore delle miniature selezionate, il pregio dei manoscritti esposti, le connessioni tra le miniature ed i codici. Se il visitatore avesse potuto trovare risposta a tali quesiti durante la visita stessa, se cioè gli strumenti tecnologici avessero realmente fornito un supporto informativo aggiunto, egli avrebbe effettivamente compreso e capito, e non solo guardato queste “piacevoli immagini”.