The Medici Villa of Poggio a Caiano

The centuries-old history of the monumental apartments

By Camilla Torracchi (Università degli Studi di Firenze)

Not far from Florence and surrounded by the hills of Tuscany the Medici Villa of Poggio a Caiano, also known as Villa Ambra, stands out.

The building was initiated by Giuliano da Sangallo at the will of Lorenzo the Magnificent and is characterized by its unusual architecture which, seen from above is in the shape of an ‘H’. It consists, in fact, of two principle wings connected by an immense hall, as opposed to the more conventional, at the time, internal courtyard. Immersed in greenery, at a more elevated height than the city center, it is a testimony to the harmonious union created by man between architecture and the surrounding natural landscape, shaped through the creation of gardens and orchards rich in diverse geometrically ordered plants.

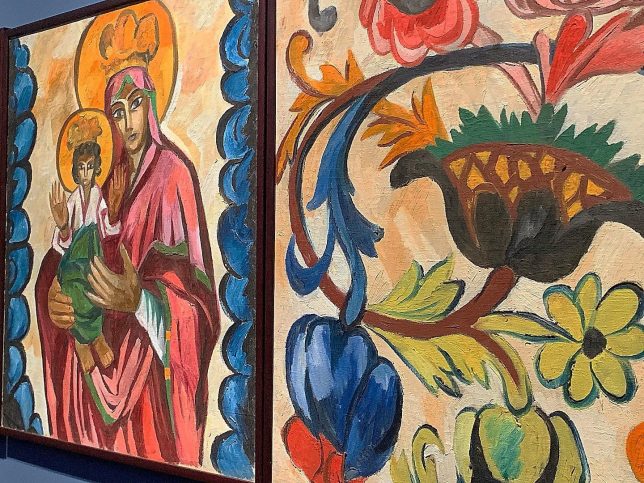

From first impact, the villa conveys the centuries old history that changed, in part, the intended floor plan in the 15th century, initially a Medicean residence, then of the Lorraine, and finally residence of Elisa Baciocchi, Napoleon’s sister, and of the Savoy dynasty. A UNESCO World Heritage site since 2013, today it also houses the Museum of Still Life, where around two-hundred works from the Medici collections are gathered and arranged according to the development of the Medicean collection itself, from the 16th to 18th centuries. It can be visited free of charge, becoming the first museum of its kind in Italy and hosting, among others, paintings by Bartolomeo Bimbi and frames by Vittorio Crosten.

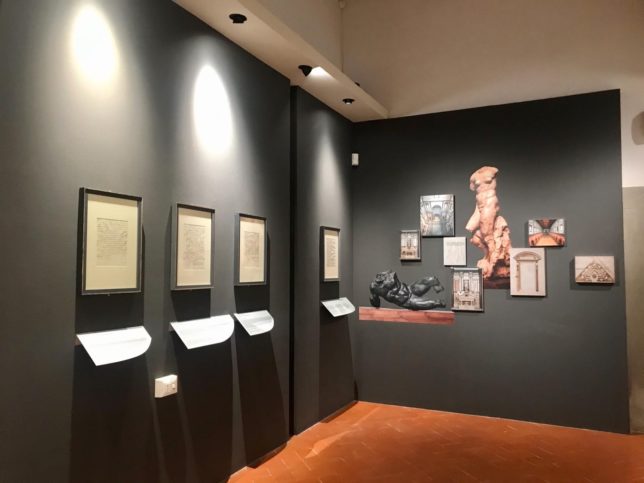

The visit begins on the ground floor, with the rooms originally designed for service functions, which correspond externally with the villa’s imposing basement. Beyond the first hall decorated in 19th century style, one enters the theater hall. The richly framed stage is visible on the wall with sumptuous decorations and a painted background, constructed in 1675 at the orders of Margherita Luisa d’Orléans, wife of Cosimo III. The billiard room follows, named for the presence of two billiard tables dating back to the time of the Savoy family, remaining the same as the era, including ceilings frescoed with cherubs and animals filling a pergola against a sky-blue background, a work of the Bolognese scenographer and painter Domenico Ferri. The last room on the ground floor is the apartment of Bianca Cappello, the second wife of Grand Duke Francesco I. Here the public has the opportunity to see the Deposition of Christ by Giorgio Vasari executed around 1561 for the villa’s chapel; also remaining onsite is the splendid Buontalenti-style fireplace and the staircase permitting access to the Grand Duke’s apartment.

The main living room is located on the first floor and named after Leo X as he was responsible for the works and decoration of this area, as can be observed by the finely crafted emblem on the ceiling recalling both the Medici family and the pontificate itself. The fresco cycle was realized by Pontormo, Andrea del Sarto, Franciabigio, and finally concluded by Alessandro Allori, prominent figures who painted scenes from ancient Rome, according to an iconographic program meant to allude to the glories of the Medici court, establishing a parallelism between the protagonists of Roman splendor and members of the Medici family.

One cannot but be awestruck by this environment, surrounded by frescos of imposing dimensions, as well as by the light that penetrates the room from two enormous windows, through which it is possible to admire the incredible panoramic Tuscan hills.

Visitors can then access the dining room with frescoed ceilings by Anton Domenico Gabbiani and the apartment of Emanuele II of Savoy, still furnished although with a limited number of items. While some of the rooms allow for free movement within the spaces, others are inaccessible, and its only possible to look from behind a red rope placed at the door, as is the case for Vittorio Emanuele II’s military camp tent or Countess Mirafiori’s room, a limit that still allows the public to understand how the villa would have appeared during the 19th century.

Finally, visitors gain access to a room housing enormous tapestries and the Della Robbia style frieze, a copy of which is exposed to the outside, below the classical tympanum placed on the façade. The visit ends just below the portico, descending from the distinctive helicoidal stairs dating back to the 19th century, and visitors are free to visit the rich surrounding gardens.

The villa can be visited free of charge and without the necessity of a reservation; every half-hour it is possible to access tours accompanied by the museum’s staff who, although not acting exactly as guides, provide necessary indications to understand the history of the building and of the various eras in which the rooms and their furnishings were realized, the majority of which in the Savoy era. The staff is very helpful in answering questions, and at complete disposal for clarifications and curiosities, making the visit both enjoyable and full of art-historical information in addition to that provided in the explanatory panels. These also act as labels for the works and furniture, since individual labels are rarely ever present, and are written in Italian, English, French and German. They are mostly small in size, thus contributing on one hand to provide the necessary information and on the other to maintain the dwelling aspect of the villa, which despite being a museum, has maintained its residential feel.

There is also a rich program of collateral events and extended opening hours that help to maintain livelihood at the villa and allow visitors a unique experience just a short distance from Florence.

(Translated by Marie-Claire Desjardin – Istituto Lorenzo De’ Medici)

La villa Medicea di Poggio a Caiano

La secolare storia degli appartamenti monumentali

Di Camilla Torracchi (Università degli Studi di Firenze)

Poco distante da Firenze e immersa fra i colli della Toscana si impone la villa medicea di Poggio a Caiano conosciuta anche come villa Ambra.

L’edificio fu iniziato da Giuliano da Sangallo per volere di Lorenzo il Magnifico e si caratterizza per un’insolita architettura che vista dall’alto risulta a forma di “H”: è costituita infatti da due ali principali comunicanti fra loro da un immenso salone, invece del più consueto, all’epoca, cortile interno. Immersa fra il verde, ad una quota sopraelevata dal centro cittadino, è testimonianza dell’unione armonica creata dall’uomo fra l’architettura e la natura circostante, plasmata attraverso la creazione di giardini ed orti ricchi di piante diverse e geometricamente ordinati.

Fin dal primo impatto, la villa tradisce la secolare storia che ha mutato in parte l’impianto pensato nel XV secolo, dimora inizialmente medicea, poi lorenese, è stata infine residenza di Elisa Baciocchi, sorella di Napoleone, e della dinastia Savoia. Patrimonio dell’Unesco dal 2013, oggi è sede anche del Museo della Natura Morta dove sono raccolte circa duecento opere provenienti dalle collezioni medicee e disposte secondo lo sviluppo del collezionismo mediceo stesso, dal XVI al XVIII secolo. Visitabile gratuitamente, si attesta come il primo museo nel suo genere in Italia e ospita fra gli altri, dipinti di Bartolomeo Bimbi e cornici di Vittorio Crosten.

Il percorso inizia dal piano terra, dagli ambienti originariamente concepiti per funzioni di servizio, che corrispondono esternamente all’imponente basamento della villa. Oltre il primo salone con decorazioni ottocentesche, si accede alla sala del teatro. È visibile il palcoscenico riccamente inquadrato nella parete con decorazioni fastose e lo sfondo dipinto, fatto costruire nel 1675 da Margherita Luisa d’Orléans, moglie di Cosimo III. Segue poi la sala del biliardo, cosiddetta per la presenza di due biliardi risalenti al tempo dei Savoia, così come dell’epoca è la volta affrescata da un pergolato abitato da puttini e animali su di uno sfondo azzurro del cielo, opera dello scenografo e pittore bolognese Domenico Ferri. L’ultimo ambiente del pian terreno è l’appartamento di Bianca Cappello, seconda moglie del Granduca Francesco I. Il pubblico ha la possibilità di vedere qui la Deposizione di Cristo di Giorgio Vasari eseguita intorno al 1561 per la cappella della villa stessa; è rimasto in loco anche lo splendido camino buontalentiano e le scale che permettevano di accedere agli appartamenti del Granduca.

Al primo piano è ubicato il salone principale detto di Leone X in quanto proprio a lui si devono le riprese dei lavori e la decorazione di questo ambiente, come ben si vede dallo stemma nella volta, finemente lavorata, che richiama sia alla casata medicea che al suo pontificato stesso. Il ciclo di affreschi fu realizzato da Pontormo, Andrea del Sarto, Franciabigio e infine concluso da Alessandro Allori, personalità di spicco che dipinsero scene dell’antica Roma, secondo un programma iconografico volto ad alludere alle glorie della corte medicea, instituendo un parallelismo fra i protagonisti dei fasti romani e i membri di casa Medici.

Non si può che rimanere colpiti da questo ambiente, circondati degli affreschi di dimensioni imponenti, nonché dalla luce che penetra nella sala dalle due enormi finestre, dalle quali è possibile ammirare l’incredibile panorama dei colli toscani.

È visitabile poi la sala da pranzo con il soffitto affrescato da Anton Domenico Gabbiani e l’appartamento di Emanuele II di Savoia, ancora arredato seppur con un limitato numero di elementi. Se in alcune stanze è consentito passeggiare e muoversi liberamente, altre sono invece inaccessibili, ed è possibile solo dare un’occhiata stando al di qua di corde rosse poste alle porte, come avviene per la camera da campo di Vittorio Emanuele II o la camera della contessa Mirafiori, limite che consente comunque al pubblico di comprendere come dovesse apparire arredata la villa nell’Ottocento.

Infine, si accede alla sala che ospita un enorme arazzo e il fregio in stile robbiano una cui copia è esposta all’esterno, al di sotto del timpano classicheggiante posto in facciata. Proprio sotto al portico termina la visita e scendendo dalle scale elicoidali distintive della villa e risalenti all’Ottocento, il visitatore è libero di poter visitare i ricchi giardini circostanti.

La villa è visitabile gratuitamente senza necessità di prenotazione; alla mezza di ogni ora è possibile accedere accompagnati dal personale del museo che, pur non svolgendo la funzione propriamente di guida, fornisce le indicazioni necessarie per poter comprendere la storia dell’edificio e le diverse epoche in cui sono stati realizzati gli ambienti e gli arredi ancora presenti all’interno, in maggioranza di epoca sabauda. Il personale è molto disponibile nel rispondere alle domande ed è a completa disposizione per chiarimenti e curiosità rendendo la visita al contempo piacevole e ricca di informazioni storico-artistiche che si sommano a quelle fornite nei pannelli esplicativi. Questi fungono anche da didascalie per le opere e la mobilia esposta, in quanto le targhette non sono quasi mai presenti, e sono scritti in lingua italiana, inglese, francese e tedesca. Sono per lo più di piccolo formato, così da contribuire da un lato a dispensare necessarie informazioni e dall’altro a mantenere l’aspetto di dimora della villa, che pur musealizzata, ha mantenuto il suo aspetto principale di residenza.

È previsto inoltre un ricco programma di eventi collaterali e aperture straordinarie che rendono ancora viva la villa e permettono di vivere un’esperienza unica a pochi passi da Firenze.

Photo Courtesy Camilla Torracchi (Università degli Studi di Firenze)